In 1928, Crystal Pool, a semi-public posh saltwater swimming pool opened at Sunset Beach in Vancouver. An advertisement in the July 16, 1929 issue of The Vancouver Sun newspaper identified that the “Sea water … warmed, filtered, purified and constantly circulated and changed … and clean sea air” added to the user’s sense of feeling fit. General admission cost 50 cents which included admission, swimsuit and towel. For 15 cents, children would receive a hot dog, Coke and bus fare to return home. Dolphin swim club that placed swimmers on Canada’s Olympic swim team trained there.

While the pool became a symbol of luxury, it existed in a time of deeply entrenched racial segregation. An article in the April 10, 1943 issue of the Vancouver News Herald reported that ““Each Tuesday morning, from 10 to 12 o’clock, Chinese Negroes and Japanese—if there happen to be any—are permitted to swim in the pool. The rest of the week their money isn’t any good.’ The pool is open to white people every day and night of the week.”

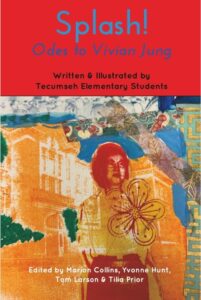

This segregation policy changed in 1945. Twenty-one-year-old Vivian Jung was hired as the first teacher of Chinese ancestry in Vancouver, however, to qualify for teaching diplomas, teachers were required to achieve swimming lifesaver certificates. Vivian went to the only public swimming pool – Crystal Pool – but was denied entry due to the segregation policy. Her swimming coach and colleagues refused to enter until Vivian was allowed to go in with them. This action sparked other acts of protest and as a result, the pool’s discriminatory policy ended within the year. Vivian taught at Tecumseh Elementary School for 35 years. Last year when she would have turned 100 years old, Vancouver poet laureate Fiona Tinwei Lam worked with staff and students at Tecumseh to create Splash! Odes to Vivian Jung, a book to raise awareness and funds for a school mural dedicated to Jung.

Across from Sunset Beach in the area now known as Vanier Park, there is a far deeper history. For generations it was a centre for Coast Salish gathering, culture, spirituality, and governance. It was an important fishing area and had a longhouse to hold potlatch ceremonies and family gatherings. In the mid-1800s Squamish people established a permanent village called Sen̓áḵw there. In 1877 Indian Reserve Commissioners officially designated this area as Kitsilano Indian Reserve No. 6 and in 1913 the reserve was dismantled and the residents were forcibly removed by barge to North Vancouver so that the city of Vancouver could expand its infrastructure. Following that, the reserve was burned down.

Subsequently, the Kitsilano Indian Reserve Beach became a sanctuary for people of colour and unofficially became known by some as Brown Skin Beach. Here, people could gather freely and swim without the racial tensions that permeated other parts of Vancouver. Other beaches were not officially segregated but black, First Nations and Asian Vancouverites did not feel welcome at them.

In 2024 CBC documented “Here’s why you probably haven’t heard of Vancouver’s ‘Brown Skin Beach’” which can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UUNeem0xxZI. In it, Pacific Canada Heritage Centre – Museum of Migration (PCHC-MoM) Director Vivian Rygnestad recalls that her father, of Japanese ancestry and born in Canada, went with his friends to this beach to swim. From this beach, he would swim across to Sunset Beach, back and forth. Rygnestad’s reflection provides an example of how these communities created their own spaces for leisure, culture, and resistance amid the prevailing climate of racial exclusion.

Remembering and reflecting on the history of Crystal Pool, Brown Skin Beach, and the efforts of individuals like Vivian Jung gives voice to the lived experiences of those who fought for dignity and inclusion. They help to broaden Pacific Canada’s collective migration narrative to include historically marginalized people’s lived experiences and create a space where all are welcomed and respected.

By Pat Parungao